It’s a staggering fact that 1 in 4 women will lose a baby during pregnancy, delivery, or infancy. And yet, many bereaved parents (and those who love them) are ill-prepared for grieving this loss. The death of a baby is, by definition, disordered. Children are supposed to accompany their parents at death, not the other way around. This departure from the natural order of things is often very isolating for the bereaved parents. While every loss is unique, there are some universalities; Exploring them along with myths about grief can be useful in helping parents understand their grief journey more realistically.

Grief is often wrongly viewed as if it were an illness that can be cured. Appropriate grieving is considered then as completing a series of tasks that somehow extinguish pain. Bereaved parents may be encouraged in a sense to deny any continued relationship with the baby or child they have lost to “recover.” This “managed care” approach is inappropriately applied to the experience of loss because loss is uniquely personal. Most importantly, viewing grief or the loss that results in suffering as something a parent can “get over” denies that the loss of a child changes the parent’s life (s) forever.

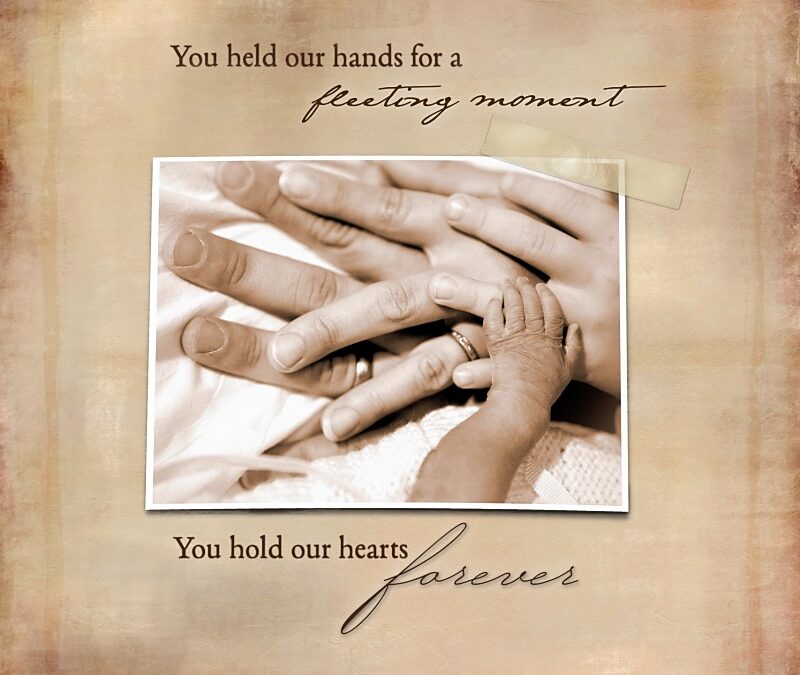

Grief is not just about the past and present. After a baby dies, a mother’s or father’s grief does not simply include the present circumstances and memories of the past, but the future the parent hoped to have with this child. Regardless of the length of the child’s life—even if entirely in utero—the longing and wondering about what life might be like with them will never go away. It’s the shattering shift of the present and the obliteration of a future. Mentioning the loss will remind bereaved parents of their pain. To paraphrase President Theodore Roosevelt: The best thing you can say is the right thing, the next best thing you can say is the wrong thing, and the worst thing you can say is nothing. A baby who has died is never much further away than the parent’s next thought. Their child and their grief are impossible to forget. Loved ones should use the baby’s name and ask questions while avoiding statements that minimize the parent’s pain. This is a difficult situation for everyone. Acknowledging that one doesn’t have the right words to adequately express sympathy can still help bereaved parents know their baby and grief are remembered.

Time heals all wounds, and parents will arrive at a place of complete closure. Time alone does not provide healing but rather what we do with time. Parents must allow themselves to grieve. Emotional healing takes time and effort, which can be mentally and physically exhausting. The intensity of pain and ongoing grief can lessen over time, but the absence will always be there. Parents must find a “new normal” when they have lost a child during pregnancy, at birth, or in the newborn period. In bereavement ministry, there is a saying that parents are more impacted by the children lost than those they had the privilege of raising. Complete closure just isn’t a possibility.

Grief is not a process of steady recovery. Grief is different for each person, but it isn’t usually linear. Bereaved individuals often experience ups and downs, feeling as if they are constantly taking two steps forward and one step back. In addition, “grief days” will occur when suddenly the experience of the loss is heavy and palpable. Often these days occur around significant holidays or the anniversary of the death but can also surface without warning or explanation. Parents should be gentle with themselves on difficult days.

Most importantly, there is no right or wrong way to grieve the death of a baby. Each parent has a unique experience since the child they grieve was utterly unique. But the hope is that every parent mourning a baby lost through miscarriage, stillbirth, or infant death be assured they are not alone and their child will always be remembered.